Dyads, Triads, and Network Dynamics

Week 4 Overview

Key Questions:

- Why do networks look the way they look?

- What processes generate network structures?

- How can we test for and model these processes?

Topics:

- Taxonomy of network formation mechanisms

- Dyadic and triadic processes

- Statistical tests for network effects

- Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs)

- Network dynamics

Why Do Networks Look the Way They Look?

Networks are not random - they exhibit consistent structural patterns:

- Clustering: Friends of friends tend to be friends

- Degree heterogeneity: Some nodes have many connections, others few

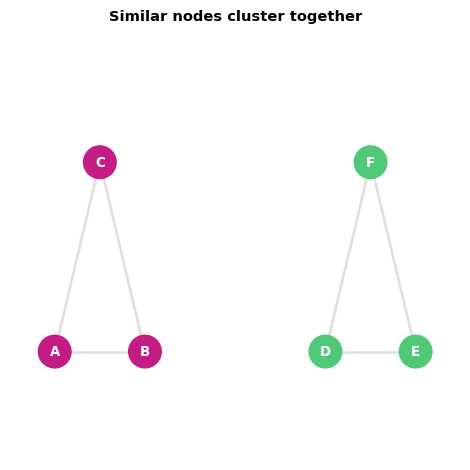

- Homophily: Similar nodes connect more often

- Small world: Short path lengths despite local clustering

Central Question: What social, biological, or physical processes create these patterns?

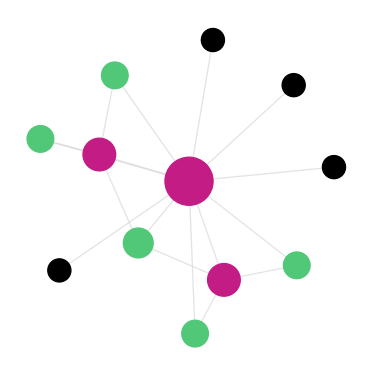

Typical network: hubs, clusters, paths

The Formation Question

Two complementary perspectives:

- Structural mechanisms: Network topology drives new connections

- Example: Triadic closure creates clusters

- Attribute-based mechanisms: Node characteristics drive connections

- Example: Homophily - similarity breeds connection

Challenge: Disentangling these effects requires sophisticated statistical models

Taxonomy of Network Effects

Major categories of network formation processes:

| Category | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dyadic | Two-node processes | Homophily, reciprocity |

| Triadic | Three-node processes | Transitivity, balance |

| Higher-order | Four+ node processes | K-cores, cliques |

| Node-level | Individual preferences | Preferential attachment |

| Exogenous | External factors | Geography, institutions |

Dyadic Processes: Definition

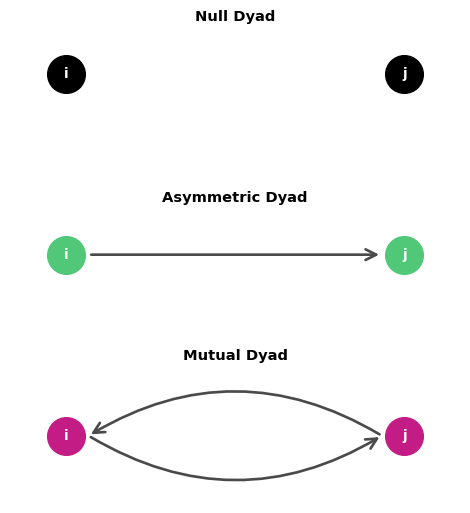

Dyadic processes operate on pairs of nodes (dyads)

A dyad can be in three states:

- Null: No connection (i → j and j → i both absent)

- Asymmetric: One-way connection (i → j OR j → i)

- Mutual: Two-way connection (i → j AND j → i)

Dyadic processes explain why specific pairs of nodes connect

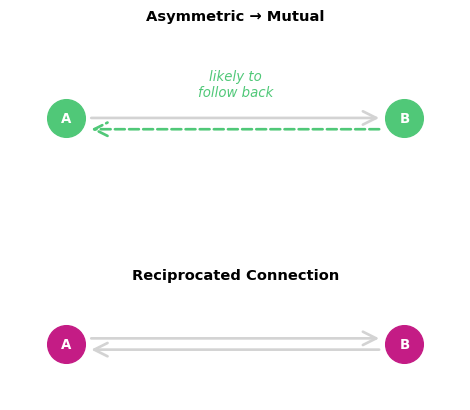

Dyadic Process: Reciprocity

Definition: The tendency for directed edges to be reciprocated

Mechanism: If i → j exists, j → i becomes more likely

Examples:

- Social media: You follow back those who follow you

- Collaboration: Co-authorship often becomes bidirectional

- Trade: Countries with import relationships develop export relationships

Statistical signature: Higher proportion of mutual dyads than expected by chance

Dyadic Process: Homophily

Definition: “Similarity breeds connection” - nodes with similar attributes connect more

Types:

- Demographic: Age, gender, ethnicity

- Behavioral: Interests, activities

- Status: Education, occupation

Formula: \(Pr(e_{ij} = 1 | phi(A_{i}, A_{j}))\)

where \(\phi\) is a similarity or distance function.

Empirical Evidence:

- Wikipedia editors (Crandall et al., 2008): Editors with similar editing patterns more likely to communicate

- University email network (Kossinets & Watts, 2006): Students taking same classes form connections at higher rates

Dyadic Process: Homophily vs Selection

Critical distinction:

- Selection (homophily): Similar people connect

- Influence: Connected people become similar

Problem: Observational data shows correlation, not causation!

Empirical example - Wikipedia editors (Crandall et al., 2008):

- Tracked similarity over time relative to first communication

- Before contact: Rapid increase in similarity (selection)

- After contact: Continued slower increase (influence)

- Both processes operate simultaneously!

Solutions:

- Longitudinal data tracking changes over time

- Statistical models that separate effects (e.g., SAOMs)

- Natural experiments

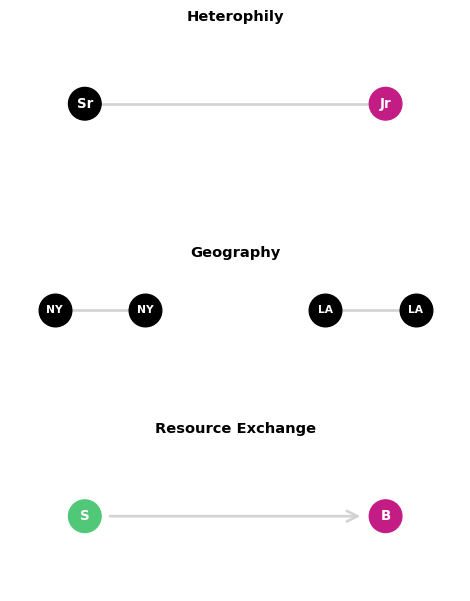

Other Dyadic Processes

Heterophily: Attraction to difference (opposite of homophily)

- Example: Dating networks, mentor-mentee relationships

Distance/Geography: Physical proximity increases connection probability

- Example: Friendship networks, communication patterns

Status homophily: Nodes connect within same status level

- Example: Corporate networks, academic citations

Resource exchange: Complementary needs drive connections

- Example: Economic networks, mutualistic relationships

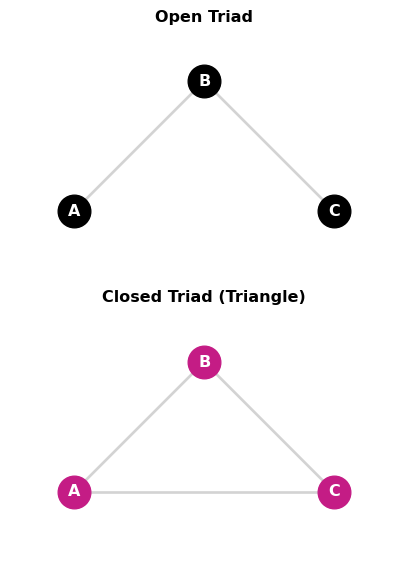

Triadic Processes: Definition

Triadic processes involve three nodes forming triangles

Key configurations:

- Open triad: A-B, B-C exist but A-C absent

- Closed triad (triangle): A-B, B-C, and A-C all exist

Core insight: The presence of two edges affects the probability of the third

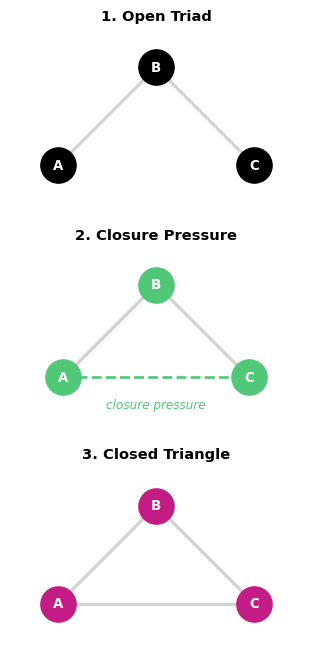

Triadic Process: Transitivity

Definition: “Friends of friends become friends”

Mechanism: If A→B and B→C, then A→C becomes more likely

Also called: Triadic closure, clustering

Examples:

- Social networks: Introduced through mutual friends

- Academic collaboration: Co-authors of co-authors collaborate

- Protein networks: Proteins interacting with same partner interact

Measurement: Clustering coefficient, transitivity ratio

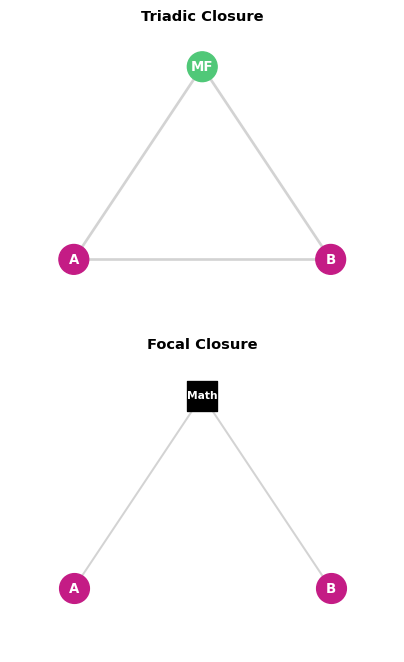

Empirical Evidence: Triadic & Focal Closure

Kossinets & Watts (2006)3: Email network at large US university

Data: ~22,000 students over one year

Key findings:

Triadic closure (shared friends):

- Probability increases roughly linearly with common friends

- Strong effect: 2 common friends > 2× effect of 1 friend

Focal closure (shared activities/classes):

- First shared class has similar effect to one friend

- Diminishing returns for additional classes

- Curve levels off (different from triadic closure)

Implication: Both structural and contextual effects matter!

3 Kossinets, G., & Watts, D. J. (2006). Empirical analysis of an evolving social network. science, 311(5757), 88-90.

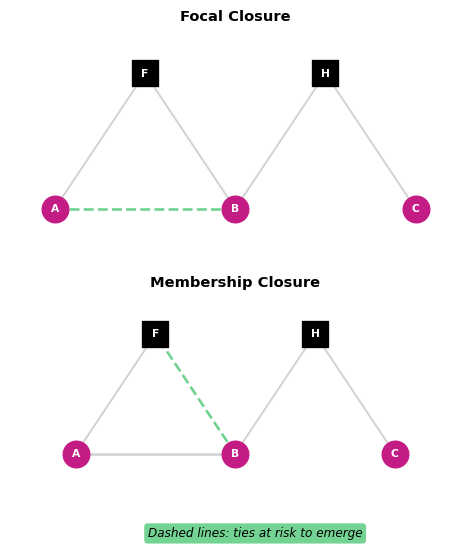

Focal vs Membership Closure: Key Distinction

Focal Closure (Easley & Kleinberg, 2010)2:

- People meet through shared activities/contexts (foci)

- Examples: Classes, workplaces, clubs, events

- Mechanism: Physical proximity + repeated interaction

- Pattern: Bipartite structure (people ↔︎ activities)

Membership Closure:

- People connect through shared group memberships

- Examples: Organizations, committees, teams

- Mechanism: Formal affiliation creates opportunities

- Pattern: Overlapping group boundaries

Key insight: Context matters as much as network structure!

2 Easley, D., & Kleinberg, J. (2010). Networks, crowds, and markets: Reasoning about a highly connected world (Vol. 1). Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

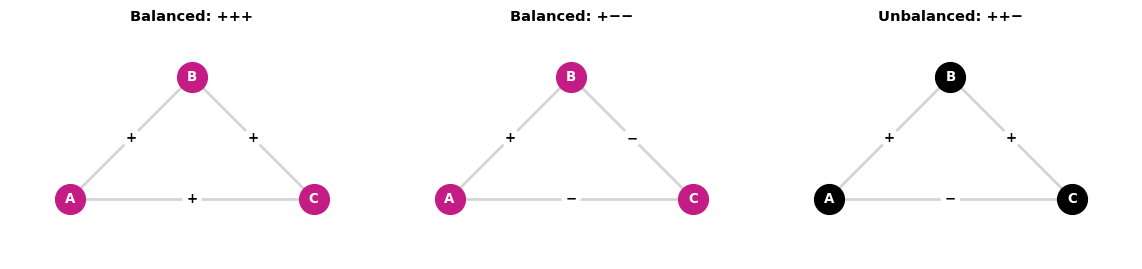

Triadic Process: Balance Theory

Structural balance (Heider, 1946): Cognitive consistency in signed networks

Balanced triangles (all relationships consistent):

- +++: Three mutual friends (stable)

- +–: Two enemies share a common enemy (stable)

Unbalanced triangles (tension):

- ++-: Friend of friend is enemy (unstable)

- —: Three mutual enemies (unstable)

Prediction: Networks evolve toward balanced states

Triadic Configurations in Directed Networks

16 possible triadic configurations (triads census)1:

Key patterns:

- 003: Empty (no edges)

- 012: One edge only

- 102: Two edges, no transitivity

- 030T: Transitive triple

- 300: Complete triangle

Different processes favor different configurations

Each tells us something about network formation mechanisms!

1 Vladimir Batagelj and Andrej Mrvar, A subquadratic triad census algorithm for large sparse networks with small maximum degree, University of Ljubljana, http://vlado.fmf.uni-lj.si/pub/networks/doc/triads/triads.pdf

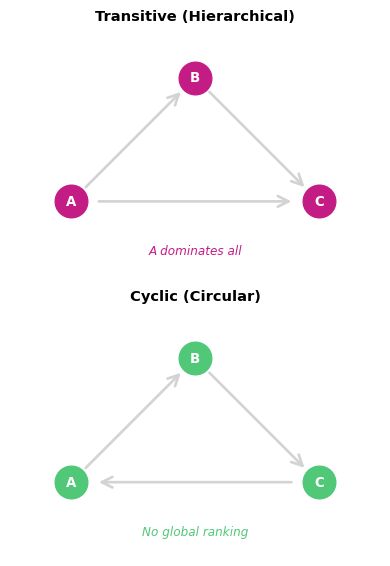

Triadic Process: Cyclicity vs Transitivity

Transitivity: A→B→C implies A→C (hierarchical)

- Creates hierarchies, rankings

- Example: Citation networks, food webs

Cyclicity: A→B→C implies C→A (circular)

- Creates exchange cycles

- Example: Rock-paper-scissors, circular status

Distinction matters for understanding network function!

Statistical Tests for Network Effects

Challenge: Network data violates independence assumptions

Classical approach fails: Standard statistical tests assume independent observations

Solutions:

- Permutation tests: Randomize while preserving structure

- Conditional Uniform Graph (CUG) tests: Compare to random graphs

- Quadratic Assignment Procedure (QAP): Correlation with permutation

Permutation Tests for Networks

Logic:

- Calculate observed statistic (e.g., clustering)

- Generate random networks preserving certain properties

- Calculate statistic on random networks

- Compare: Is observed value extreme?

Key decision: What to preserve when randomizing?

- Node degrees?

- Number of edges?

- Dyad distributions?

Graph Uniform Test

In network analyses, permutation tests are often called Graph Uniform Tests.

Purpose: Test whether an observed network differs significantly from random networks

Fundamental Aspects:

- Null Hypothesis: Observed network is drawn from a uniform distribution of graphs

- Test Statistic: Any network property (density, clustering, centralization, etc.)

- Procedure:

- Calculate test statistic on observed network

- Generate many random networks with same size and density

- Calculate test statistic for each random network

- Compare observed statistic to distribution of random statistics

Interpretation: - p < 0.05: Network structure differs significantly from random - p ≥ 0.05: Cannot reject that network is random

Applications: Detect non-random patterns in social networks, communication networks, biological networks

QAP Regression

Quadratic Assignment Procedure: Test relationship between network matrices

Use case: Does network Y depend on network X?

Example: Does friendship (Y) depend on geographic proximity (X)?

Procedure:

- Regress Y on X, get coefficient β

- Permute rows/columns of Y simultaneously

- Repeat regression, get β*

- Repeat 1000+ times

- P-value: proportion where |β*| > |β|

Advantage: Accounts for network dependencies

Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs)

Core idea: Model probability of observing a network as function of its features

Form: \[P(Y = y) = \frac{1}{\kappa} \exp\left(\sum_k \theta_k s_k(y)\right)\]

Where:

- \(Y\): Random network

- \(s_k(y)\): Network statistics (edges, triangles, etc.)

- \(\theta_k\): Parameters (effects to estimate)

- \(\kappa\): Normalizing constant

ERGM: Intuition

Think of it as logistic regression for networks

Instead of: P(person votes yes) = f(age, income, …)

We have: P(network has this structure) = f(edges, triangles, homophily, …)

Key insight: Model entire network as outcome, not individual ties

Advantages:

- Tests multiple mechanisms simultaneously

- Controls for confounding effects

- Provides effect sizes, not just significance

Common ERGM Terms

| Term | Effect | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

edges |

Density | Overall connection probability |

mutual |

Reciprocity | Tendency for reciprocation |

triangle |

Transitivity | Tendency for closure |

nodematch("attr") |

Homophily | Same-attribute connection |

nodecov("attr") |

Attribute effect | Node attribute influence |

gwesp |

Shared partners | Weighted transitivity |

Model specification: Choose terms based on theory!

ERGM: Interpretation

Positive coefficient (θ > 0): Configuration is more likely than chance

Negative coefficient (θ < 0): Configuration is less likely than chance

Example interpretation:

edges: -2.5 (low baseline density)

mutual: 1.8 (strong reciprocity)

triangle: 0.4 (moderate transitivity)

nodematch("gender"): 0.6 (gender homophily)Reading: Controlling for density, reciprocity, and triangles, same-gender ties are more likely

ERGM: Challenges

Degeneracy problem: Some specifications lead to extreme networks

- All edges or no edges

- Complete clustering or no clustering

Computational challenge: Calculating κ is often intractable

Solutions:

- Use geometrically-weighted terms (GWESP, GWDSP)

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimation

- Careful model specification and testing

Network Dynamics Models

So far: Models of static networks (single time point)

Reality: Networks evolve over time

Dynamic approaches:

- Temporal ERGMs: ERGMs on network changes

- Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models (SAOMs): Actor-driven change

- Relational Event Models (REMs): Continuous-time interactions

Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models

Key assumption: Actors make rational decisions about ties

Process:

- Actors get random opportunities to change ties

- They evaluate potential changes via utility function

- They choose change that maximizes utility

Utility function includes:

- Structural preferences (transitivity, reciprocity)

- Attribute preferences (homophily)

- Costs and benefits

Software: RSiena package in R

Advantage: Separates selection from influence effects!

```

Comparing Modeling Approaches

| Approach | Time | Question | Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERGM | Static | What structure? | Multiple mechanisms |

| SAOM | Panel | How does it change? | Selection vs influence |

| REM | Continuous | When do events occur? | Precise timing |

| TERGM | Discrete steps | What changes? | Network evolution |

Choice depends on:

- Data structure (cross-sectional vs longitudinal)

- Research question (structure vs process)

- Computational resources

Summary: Key Takeaways

Network structure emerges from systematic processes, not randomness

Dyadic processes (reciprocity, homophily) explain pairwise connections

Triadic processes (transitivity, balance) explain local clustering

Statistical tests must account for network dependencies (permutation, QAP)

ERGMs model network probability as function of multiple mechanisms

Dynamic models capture how networks evolve over time

Next steps: Applying these models to real data!

Further Reading & Resources

Core texts:

- Lusher, Koskinen & Robins (2013). Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks

- Snijders, van de Bunt & Steglich (2010). “Introduction to SAOMs”

- Wasserman & Faust (1994). Social Network Analysis

Software:

statnetpackage (R): ERGMsRSienapackage (R): SAOMsigraphpackage (R/Python): Basic network analysis

Online resources: INSNA workshops, Summer institutes