library(igraph)

set.seed(42)

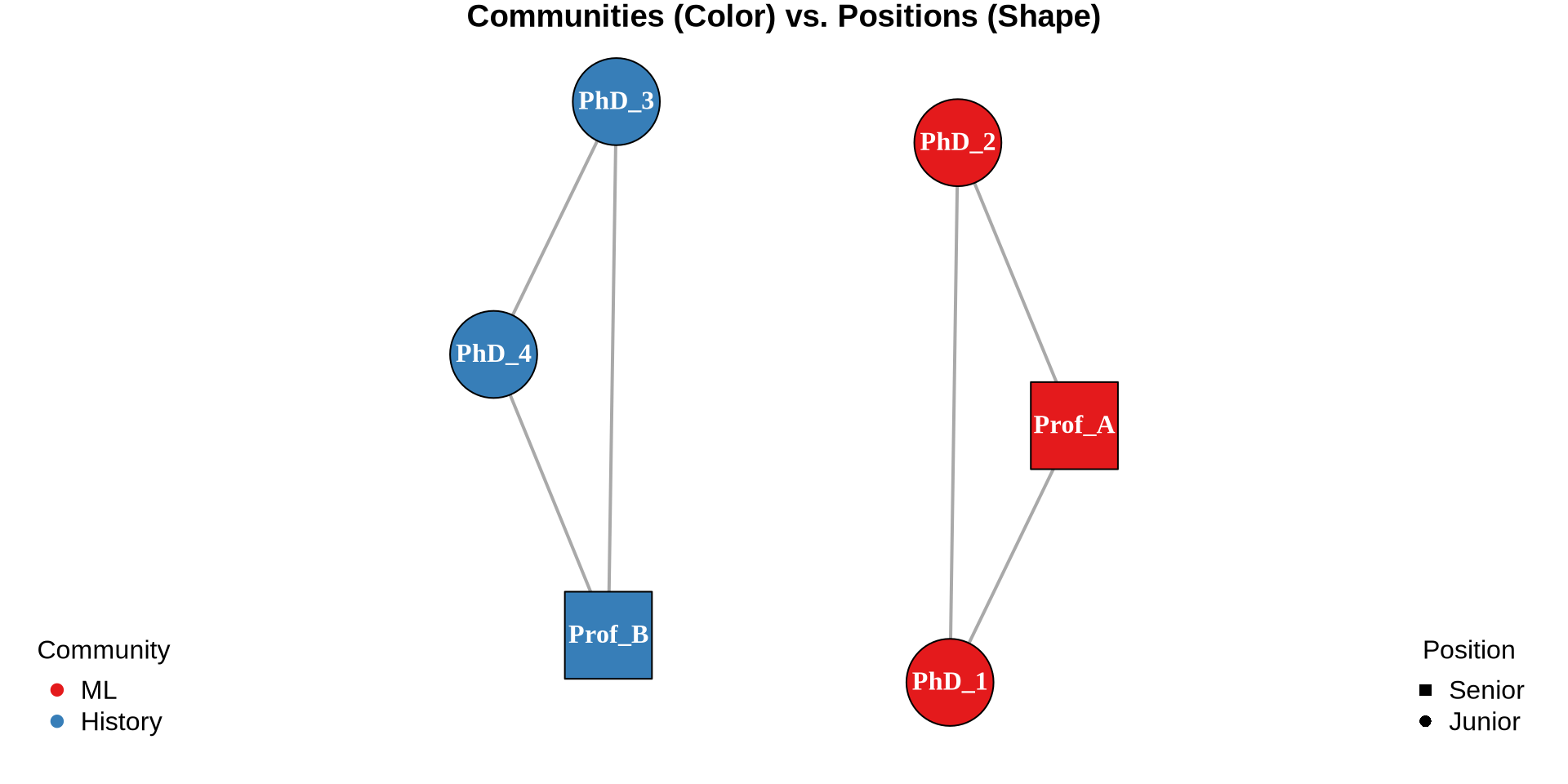

# Create a network with clear positional structure

# 3 "leaders" (high out-degree), 6 "followers" (high in-degree), 3 "isolates"

g <- make_empty_graph(n=12, directed=TRUE)

g <- add_edges(g, c(

1,4, 1,5, 1,6, 1,7, # Leader 1 → Followers

2,5, 2,6, 2,7, 2,8, # Leader 2 → Followers

3,6, 3,7, 3,8, 3,9, # Leader 3 → Followers

4,1, 5,2, 6,3 # Some followers → leaders (feedback)

))

adj <- as.matrix(as_adjacency_matrix(g))

# Step 1: Compute Similarity Matrix (Correlation of tie patterns)

similarity <- cor(t(adj)) # Transpose to correlate rows

similarity[is.na(similarity)] <- 0 # Handle nodes with no ties

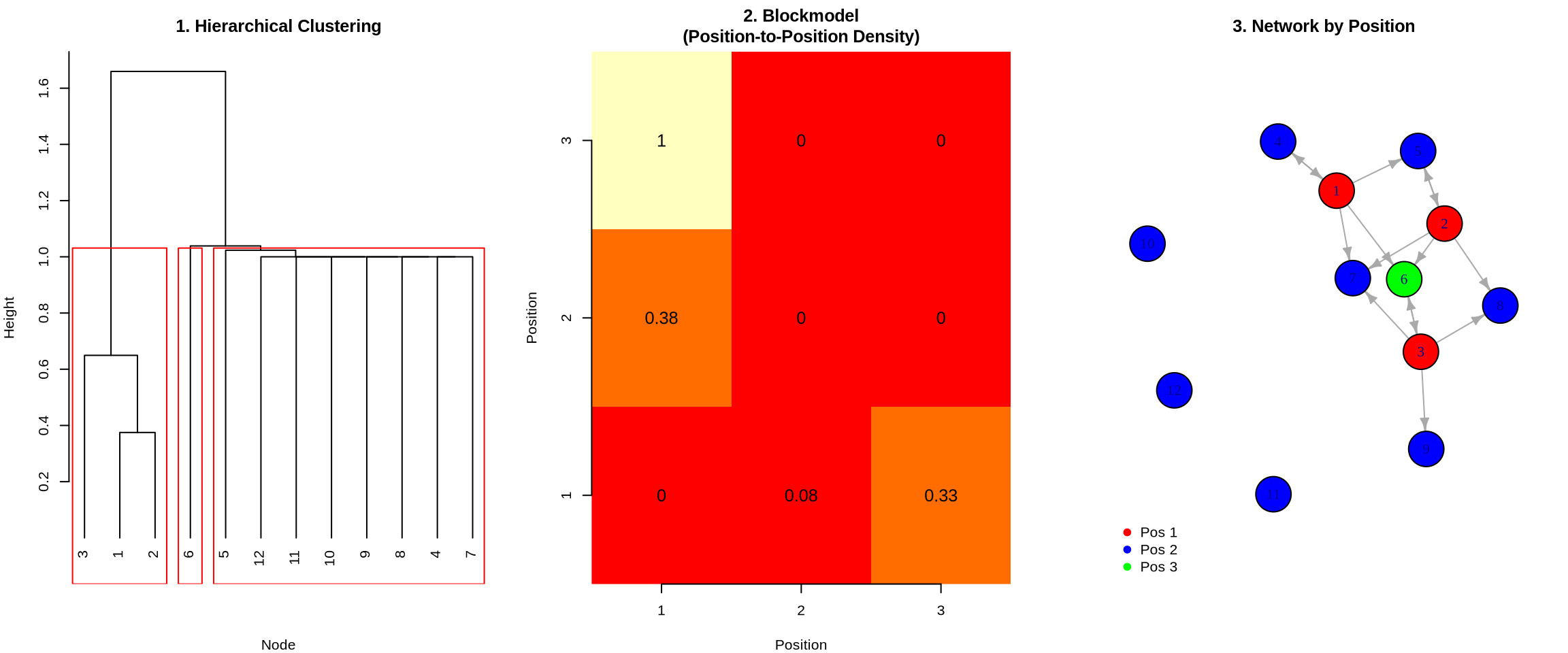

# Step 2: Hierarchical Clustering

dist_matrix <- as.dist(1 - similarity) # Convert similarity to distance

hc <- hclust(dist_matrix, method = "ward.D2")

positions <- cutree(hc, k = 3) # Cut into 3 positions

# Step 3: Create Blockmodel (Image Matrix)

n_pos <- max(positions)

blockmodel <- matrix(0, nrow = n_pos, ncol = n_pos)

for(i in 1:n_pos) {

for(j in 1:n_pos) {

block <- adj[positions == i, positions == j, drop=FALSE]

if(length(block) > 0) blockmodel[i, j] <- mean(block)

}

}

# Visualize the three outputs

par(mfrow=c(1,3), mar=c(4,4,3,2))

# 1. Dendrogram (Hierarchical Clustering)

plot(hc, main = "1. Hierarchical Clustering", xlab = "Node", sub = "", hang = -1)

rect.hclust(hc, k = 3, border = "red")

# 2. Image Matrix (Blockmodel)

image(1:n_pos, 1:n_pos, blockmodel, col = heat.colors(10),

main = "2. Blockmodel\n(Position-to-Position Density)",

xlab = "Position", ylab = "Position", axes = FALSE)

axis(1, at = 1:n_pos); axis(2, at = 1:n_pos)

text(expand.grid(1:n_pos, 1:n_pos), labels = round(blockmodel, 2), cex = 1.2)

# 3. Network colored by position

V(g)$color <- c("red", "blue", "green")[positions]

plot(g, vertex.size = 20, edge.arrow.size = 0.5,

main = "3. Network by Position",

vertex.label = 1:12)

legend("bottomleft", legend = paste("Pos", 1:3),

col = c("red", "blue", "green"), pch = 19, bty = "n")