Network Analysis Glossary

Essential Terms and Concepts

Core Network Components

Graph

A graph is a mathematical structure consisting of a set of objects (vertices) and a set of connections (edges) between pairs of these objects. In network analysis, graphs provide the fundamental framework for representing relationships and interactions between entities. Graphs can be directed (edges have direction) or undirected (edges have no inherent direction).

\[ G = {v, e} \]

where

\[v = [v_1, v_2, ..., v_i, ... v_n]\]

and

\[e = [(v_1, v_2), (v_1, v_i), ..., (v_i, v_j), ..., (v_j, v_n)]\]

Vertices (Nodes)

Vertices (also called nodes) are the fundamental units or entities in a network. They represent the objects being studied, such as:

- People in social networks

- Computers in technological networks

- Proteins in biological networks

- Cities in transportation networks

Each vertex can have attributes (e.g., age, location, type) that provide additional information about the entity it represents.

Edges (Links/Ties)

Edges (also called links or ties) represent the connections or relationships between vertices. They encode the interactions, associations, or dependencies between entities in the network. Edges can have various properties:

- Direction (directed vs. undirected)

- Weight (strength of connection)

- Type (multiple relationship types)

- Temporal information (when the connection exists)

Network Relationship

A network relationship defines the nature of connections between entities in a network. These relationships determine:

- What constitutes a connection (e.g., friendship, communication, transaction)

- How connections are measured or identified

- Whether relationships are symmetric or asymmetric

- The meaning and interpretation of network patterns

Network Types

One-mode vs Two-mode Networks

One-mode Networks

One-mode networks (also called unipartite networks) contain only one type of vertex. All connections occur between vertices of the same type. Examples include:

- Friendship networks (people connected to people)

- Citation networks (papers citing papers)

- Trade networks (countries trading with countries)

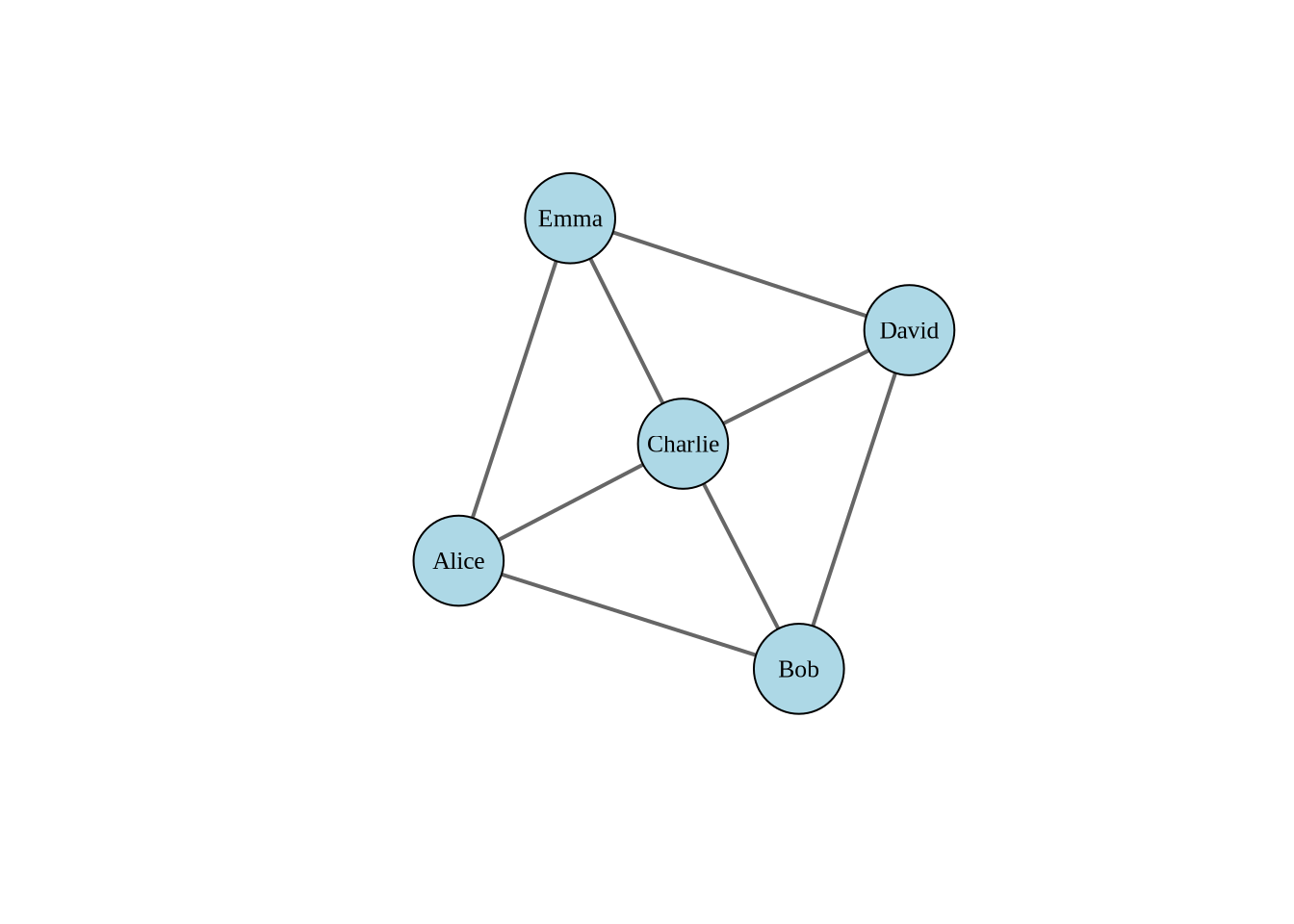

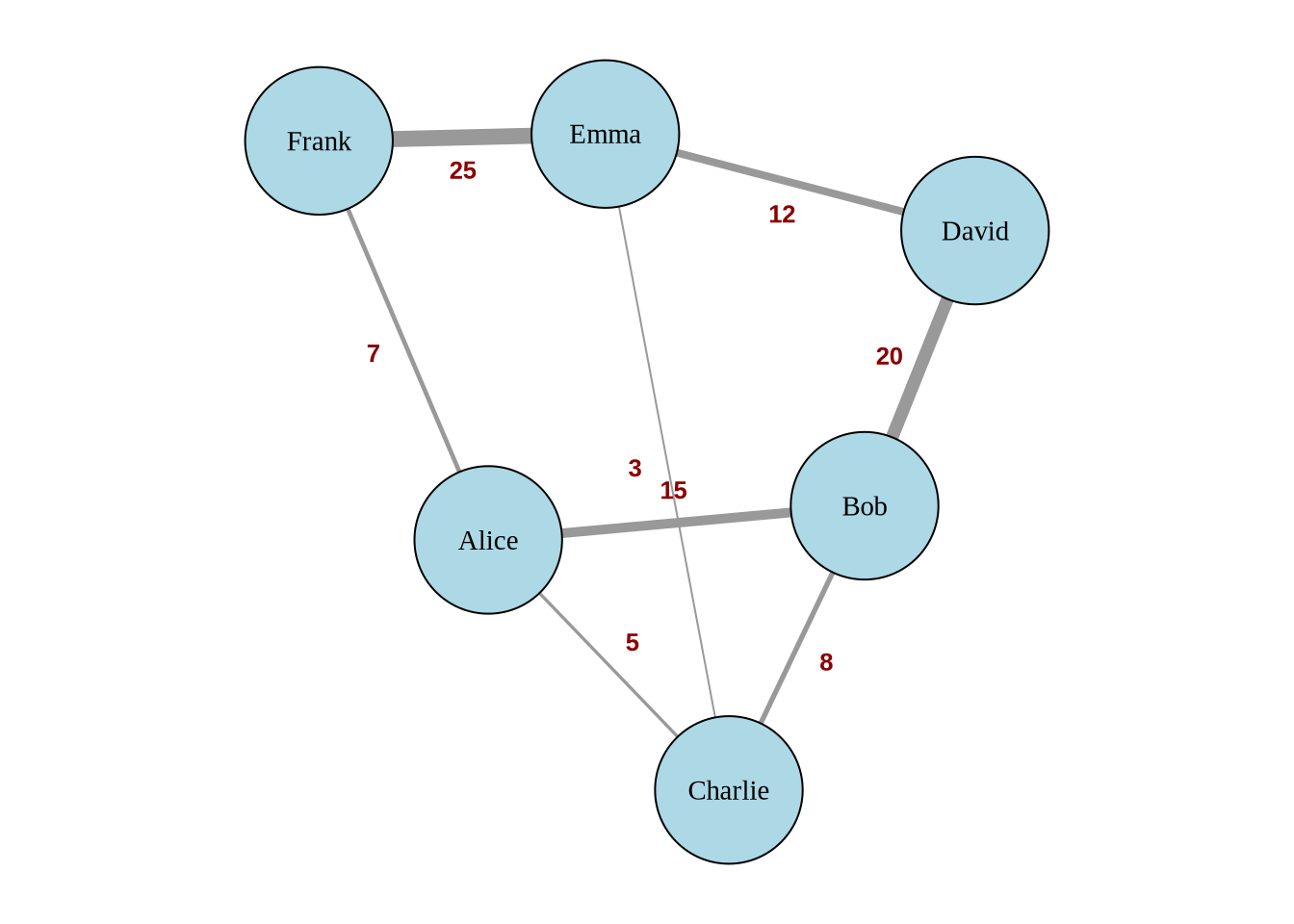

Here’s an example of creating a one-mode network visualization concerning a collaboration network among five co-workers:

Directed Vs Undirected Networks

Directed networks (also called digraphs) have edges with a specific direction, indicating asymmetric relationships where the connection flows from one vertex to another. Examples include:

- Email networks (sender → receiver)

- Citation networks (citing paper → cited paper)

- Food webs (predator → prey)

- Twitter follower networks (follower → followed)

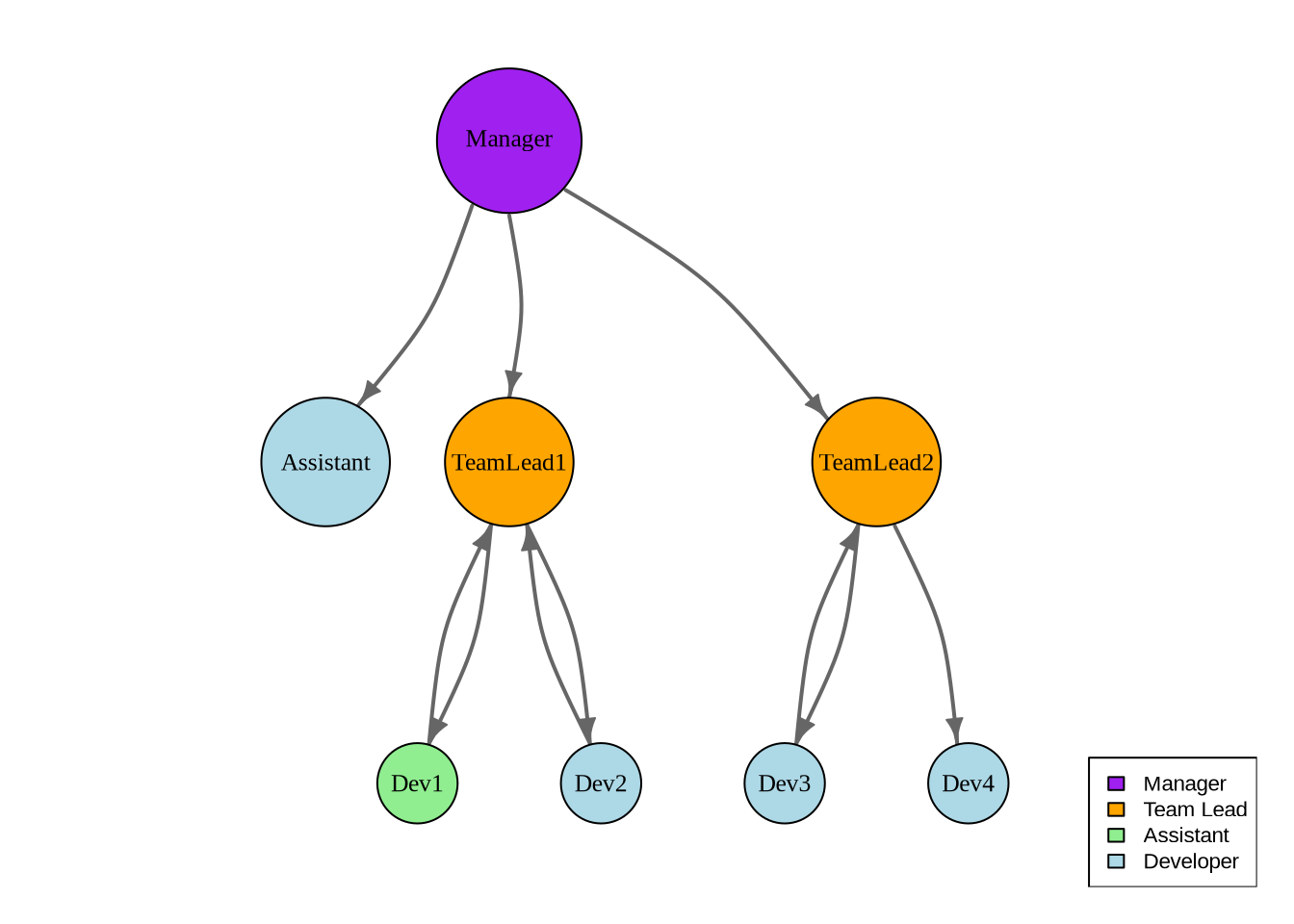

Here’s an example of a directed network:

Undirected networks have edges without direction, representing symmetric relationships where connections are mutual. Examples include:

- Friendship networks (mutual friendships)

- Co-authorship networks (collaborations)

- Infrastructure networks (roads, power grids)

- Protein interaction networks

The choice between directed and undirected representation depends on whether the relationship being modeled is inherently asymmetric or symmetric.

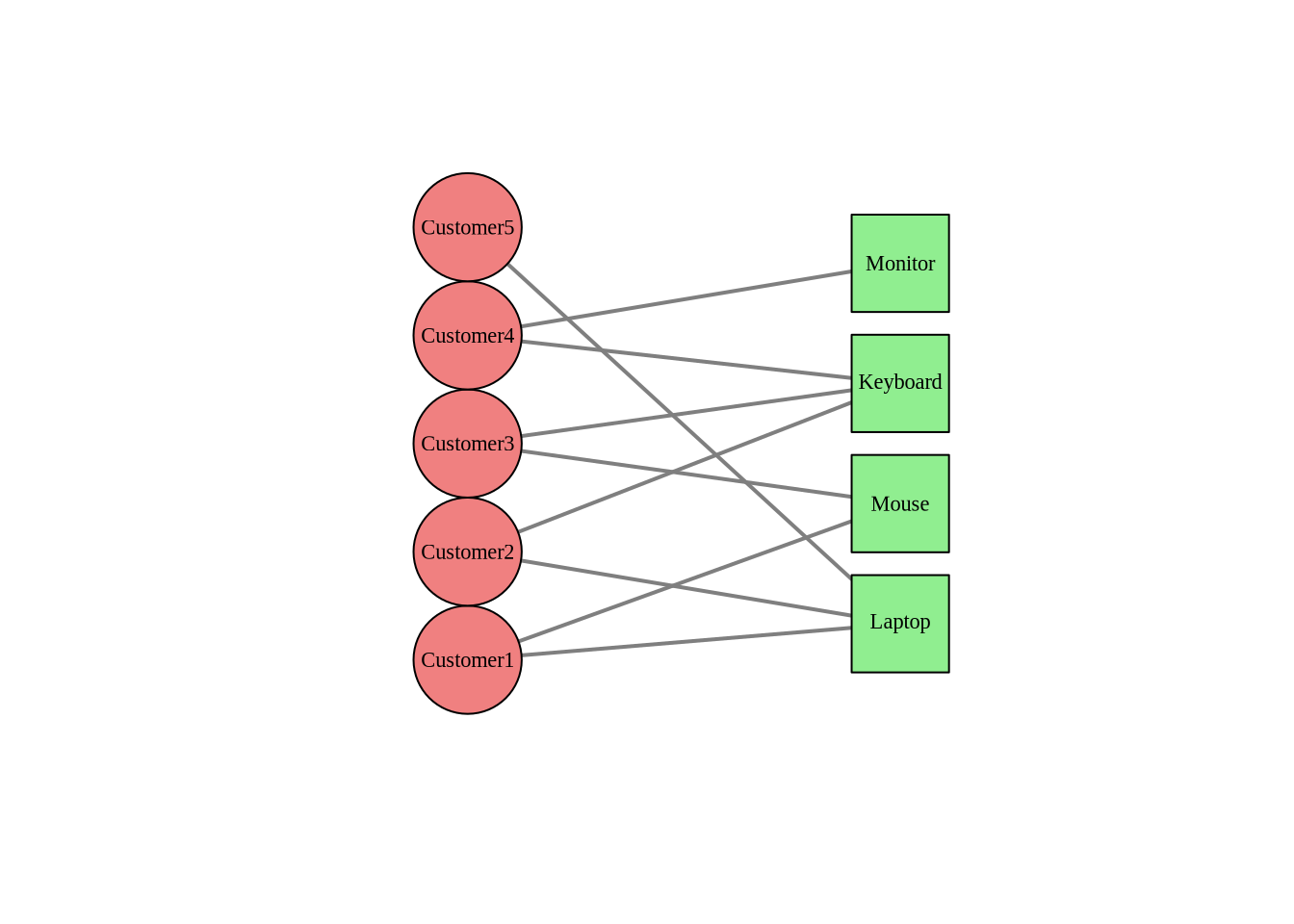

Two-mode Networks

Two-mode networks (also called bipartite networks) contain two distinct types of vertices, and edges only connect vertices of different types. Examples include:

- Actor-movie networks (actors connected to movies they appear in)

- Author-paper networks (authors connected to papers they wrote)

- Customer-product networks (customers connected to products they purchased)

Here’s an example of a two-mode purchasing network:

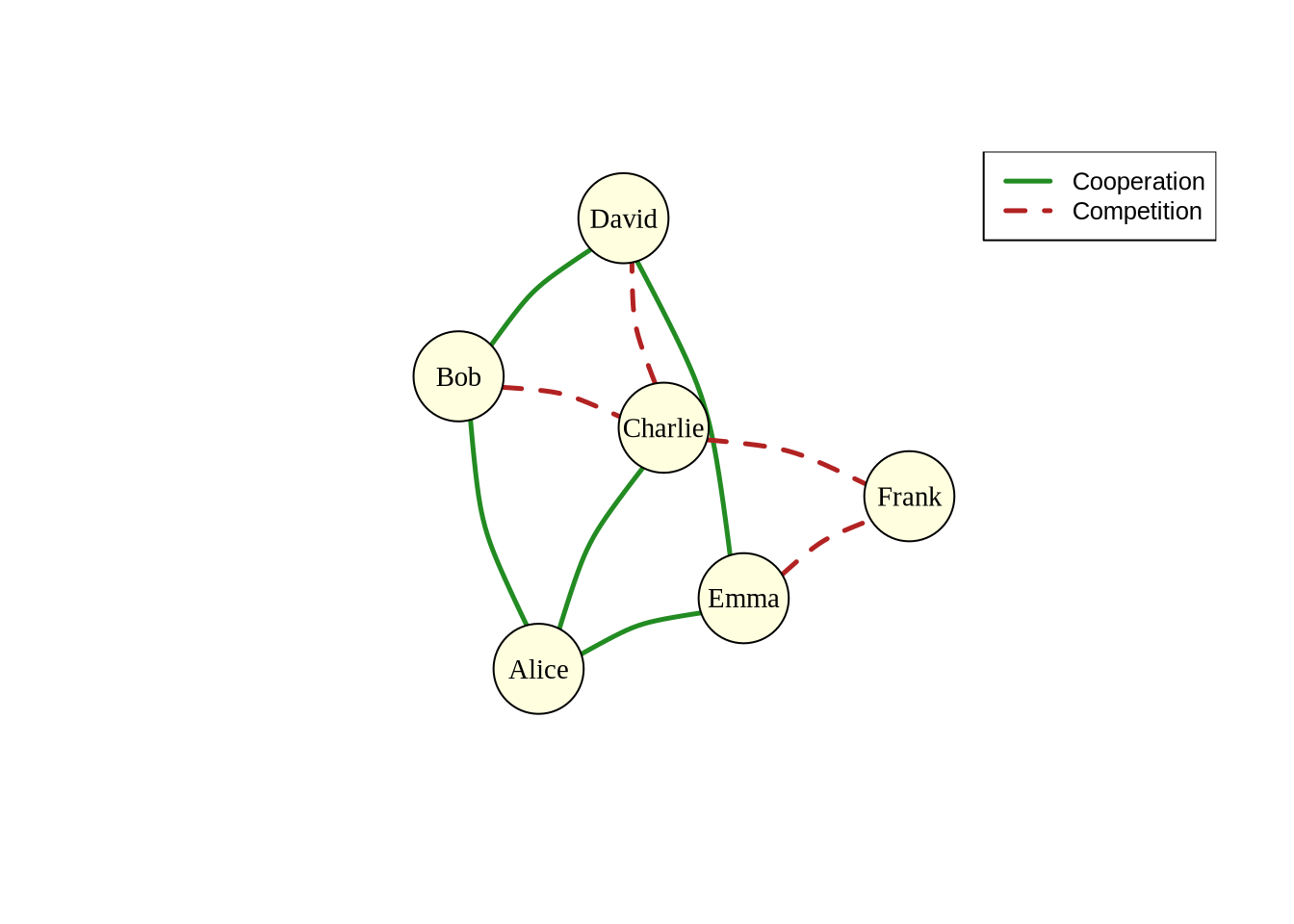

Signed Networks

Signed networks are networks where edges carry positive or negative values, representing different types of relationships:

- Positive edges: friendship, alliance, cooperation

- Negative edges: animosity, conflict, competition

Signed networks are particularly useful for studying:

- Social balance theory

- Coalition formation

- Conflict dynamics

- Opinion polarization

Here’s an example of a signed social network like cooperative Vs. competitive ties among co-workers:

Weighted vs Unweighted Networks

Weighted Networks

Weighted networks have edges with numerical values (weights) representing the strength, frequency, or capacity of connections. Examples include:

- Communication networks (number of messages exchanged)

- Transportation networks (traffic volume or distance)

- Neural networks (synaptic strength)

- Financial networks (transaction amounts)

Here’s an example of a weighted communication network:

Unweighted Networks

Unweighted networks (also called binary networks) have edges that simply indicate the presence or absence of a connection. All edges are treated equally, focusing on the topology rather than connection strength. These are simpler to analyze but may lose important information about relationship intensity.

Network Substructures

Dyads

A dyad is the simplest possible network substructure, consisting of a pair of vertices and the possible edge(s) between them. In directed networks, dyads can be classified as:

- Null dyad: no connection in either direction

- Asymmetric dyad: connection in one direction only

- Mutual/Reciprocal dyad: connections in both directions

Dyadic analysis examines pairwise relationships and forms the foundation for understanding reciprocity and basic network patterns.

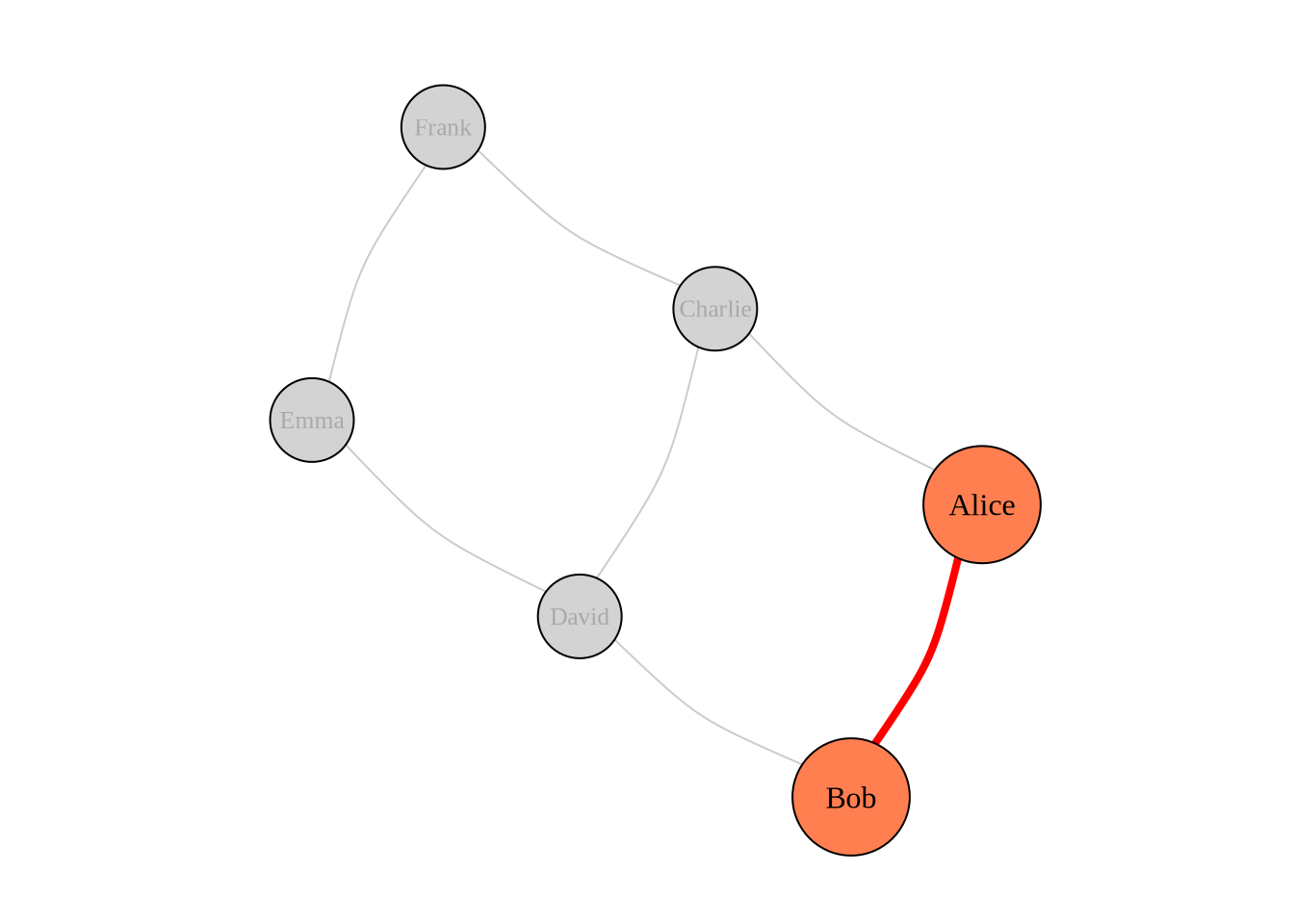

Here’s a visualization showing a dyad within a larger network:

Triads

A triad consists of three vertices and the possible edges among them. Triads are fundamental for understanding:

- Transitivity (“friend of a friend” patterns)

- Structural balance

- Clustering tendencies

- Local network motifs

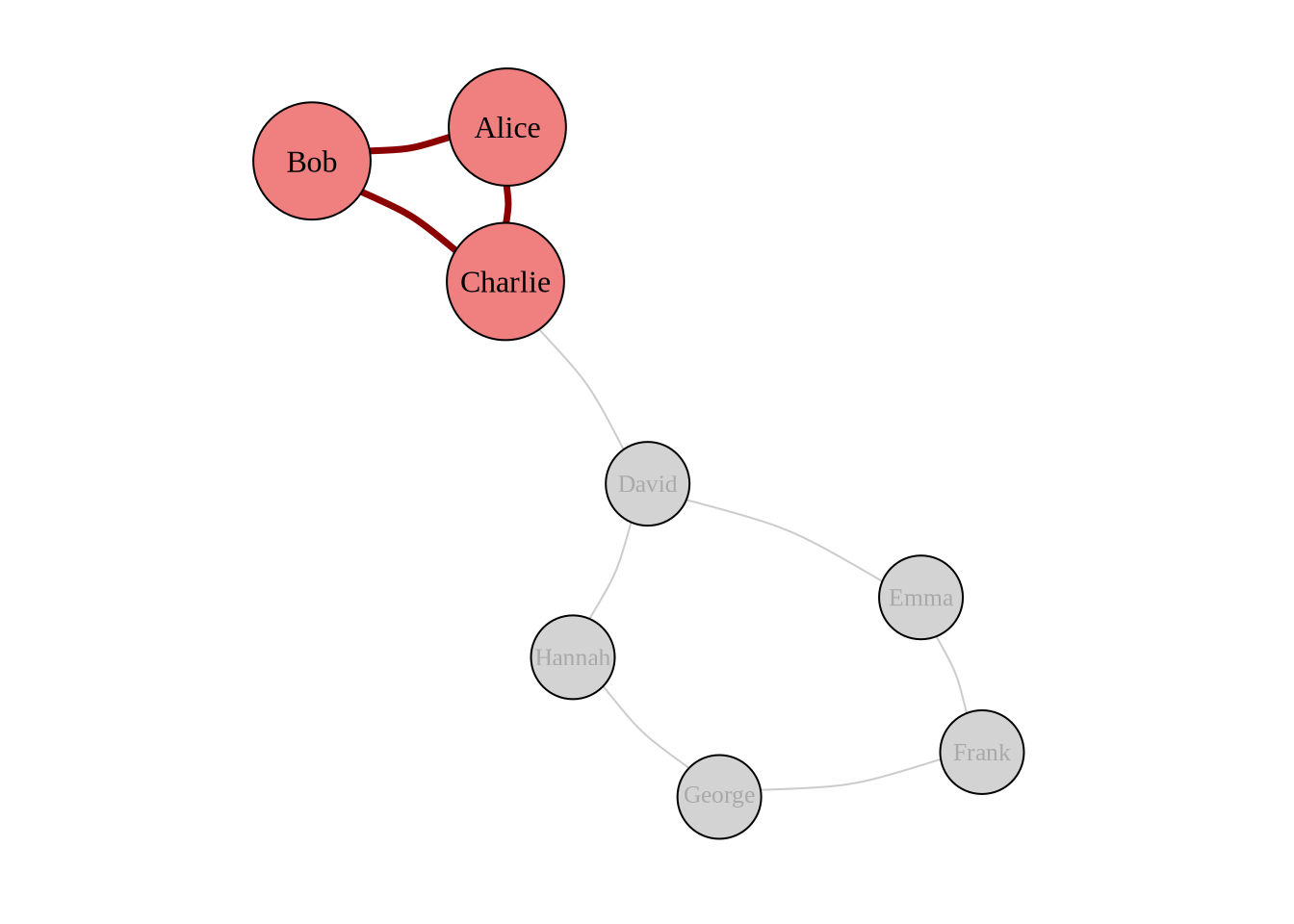

Here’s a visualization showing a triad within a larger network:

We will deal with these in weeks 4 and 5.